Chapter 8

Uncle Nando’s called El Cabro—an awful way of saying he’s gay. That’s the reason my dad’s cartel ostracized him so: stripped him of his birthright and left him alone, home on the range, in that casita on the edge of El Rancho de las Cabras. The Cabra cartel still funnels him funds from the family businesses cuz he’s my uncle after all. He saves his pesos for Roz, we think, because he’s frugal as a monk, except when he has visitors from CDMX and they get all flamboyant with drag shows on the ranch’s lucha libre ring. Then Nando’s rich and luxurious. And Rico would be furious.

My father, Rico, is not to know about the drag shows. They’re super secret. Rico, my father, built the ring for private luchador fights—his leisure and inspiration. Little does he know Nando does huge drag shows in that precious ring of his.

At first, they thought Uncle Nando never recovered from Bimori’s childbirth death, but his despondency dug deeper in his soul. He had hid his homosexuality for so long from his brother, from his family, from us girls, from the cartel that could crush him for it. He’d become a passive pawn in the Cabra cartel letting his little brother take the lead. So, of course, his true self was bound to burst forth—first in binge trips to Ciudad de Mexico engaging in the secret gay scenes there, then bringing drag to el ranchero—to Rico’s lucha libre ring—with over-the-top drag fests that grew and grew under Rico’s nose without him knowing.

Then his sexuality was torn from him in a cartel humiliation that killed the lover he kept in the casita where he continues to be held captive with the daughter he loves but regrets, Rosalinda. Massively emasculated, he rots in that modest home. So Roz lives with me. He perks up only when a drag show is planned—and then he goes all out, becomes someone completely other—a lover of life, luxury and the lion-hearted lovelies of his ilk. From la ciudad de Mexico, drag queens to third gender Muxes—all arrive at these covert clandestine desert drag orgies at el Rancho de las Cabras, led by el Cabro Nando himself!

Roz’s mom’s family had worked at el Rancho de los Cabras for generations. Bimori was around from infancy to womanhood. Even though, well maybe because, she was separated from her Rarámuri community, one Tarahumara man stalked and struck her leaving her pregnant without marriage prospects other than Nando. The scenario did not represent a rare occasion among the Rarámuri whose vocabulary includes no word for love. But Bitmori’s pregnancy became the ideal antidote to Nando’s dilemma as a closeted queer—he could claim he contributed to the family stock while not losing footing with the fact he was a fag. Plus, he liked Bimori a lot. They were friends since childhood, though Rico resented that. Anyhow, that’s how Rosalinda came about.

Most say Bimori knew of Nando’s true amores but always loved him regardless. Roz’s birth shoulda been foolproof. Instead Bimori bled. She bled and bled and bled on Roz’s birth bed until all that was left was Rosalinda’s cry. Sangre.

I was born later that same day to Anna in the next room. Anna, americana, was headstrong. She believed Rico murdered her dear Bimori. Bimori’s death could have been hers, she believed. Anna also maintained the bad brother’s bad blood was in her baby, me. She saw that vulnerable day as her only way to escape, so she rose from her birthing bed and fled. On foot. Streams of our shared bloodstream streamed the land. Rico’s armed men followed the red path where it led. The blood stopped at the road beyond el ranchero where she must have gotten a ride. She returned to the States, it’s assumed. She never looked back. We, daughters of these brothers with very different mothers, were raised by our abuelos y mujeres hired by our fathers.

It is doubtful these brothers wished for daughters. But there we were, two gurgling baby girls. Without mothers around to give us names, the brothers chose to name us after their mother, Celia Rosalinda. One name was given to each of us. Nando favored Rosalinda and claimed it for his daughter. Rico received me, Celia.

Then, when Uncle Nando’s sexual preference surfaced as a spoken fact around the ranch, when whispering about him stopped and folks began to speak aloud of his unnatural life following Bimori’s death, Rico–who undoubtedly knew his brother’s preferences better than anyone else on earth–forced Fernando with infant Rosalinda from the Hacienda Hisperia to that casita at the edge of the Rancho de las Cabras.

Rosalind is the more striking of us two, taller and more graceful but sturdy and strong. She’s a jaguar, I’m a fox. We’re both precocious, more than mildly smart, but I am shorter and somewhat plainer—at least not as striking, let’s say that. My mother had me here at the Hacienda Hisperia where she’d evidently dawdled for a couple years as my father’s teenaged affair and Bimori’s best friend beside Nando. They played princesses at Hisperia, much the way Roz and I do now. Until their house of cards crumbled when we arrived.

Rosalinda spends far more time at Hacienda Hisperia with me than with her father Fernando in that casita. First it was easier for childcare and meals. But we bonded as sisters for life.

We rule Hisperia, the red-roofed roost de tejas redondeada y roja. Built by the abuelos de nuestras abuelos, tal vez their grandparents caliche brick by caliche brick, expanded upon by each generation with pine details like the two-story porches facing the verdant courtyard we pass through wherever we need to go and our balcones overlooking the pine forest y montañas beyond where the sun sets on one side of the edifice and rises on the other. We sleep on the sunset side.

When I was small, I felt myself superior to Rosalind—which was very very wrong. I believed myself to be the more privileged because l rightly lived at Hisperia while Roz “visited” me here from her hovel. In truth, my entitlement stemmed from my envy of Roz—the stronger, more graceful girl. She was the better tomboy than me—by far.

It seemed unfair and I punished her for it with my superiority. Nonetheless, we loved each other as deeply as two girls can, though evil antics occasionally bubbled up in me against my sweet cuz. We grew from toddlers to girlhood BFFs to teenage girlfriends and now we’re lovers: Shhhhh! But there has lurked a lifelong violent streak between us—hairpulling girl fights, physical love fights, teenage bitchslaps. The rest of the time we love each other deeply and unconditionally. We’ve always been inseparable.

And now I am so deeply in love with her. Dearer than the natural bond of sisters, some may soon be saying. My body needs her sustenance. I constantly crave crawling up inside her. Curling my limbs around her. Eliciting from her those desert creature sounds, short high cries, snakelike sighs, secreting juices, freeing fluids, hissing kisses, lascivious licks, reptilian stretches, spiderlike suspension, shapes birds make—so amazing. We’re the oasis princesses we were meant to be. Queenhood here at the Hacienda Hisperia.

I hear hay una Hisperia en California. It’s also in the desert. The word means “western land.” Hesperus was an ancient Greek god of the west and once upon a time the boot of Italy was called “Hisperia” by Greeks and Romans. All good omens. Hisperia is mentioned only once in Shakespeare’s works: in As You Like It, as Celia’s handmaid—she has no lines, nor is she seen. Hacienda Hisperia has been my handmaid since birth. I love her dearly. But I love Roz more.

Hisperia hushes the wind by spinning wishes in dizzying dusty circles, swaying the poppies, the pines and the pot plants. She shares her secrets upon secrets upon secrets with the scenery surrounding us, but Roz and I are the only ones listening.

Hisperia often whispers about my father, Rico, who I and others call El Cabron—that bastard. He’s one of narcoculture’s major Mexican kingpins. His is the Cabra cartel. He’s who’s trapped us here in the grandly hospitable Hacienda Hisperia inherited from his ancestors and ours.

Pinche cabron.

PRESENTATION:

Interfaith Welcome Coalition ~ Bus Station Ministry (Michelle Rumbaut)

Chapter 18

We disembark our bus from Dilley, in a line, of course. It is hot and sunny. We walk one by one into the Greyhound Station. My traditional Tarahumara dress abuelita made me that the desert wore threadbare is balled up tight in an HEB bag I carry. I wear sweat pants, an oversized t-shirt and tennis shoes donated by the Dilley Immigration Detention Center, or donated to them by some buena fuerza incognita cuz I’m not so sure the Dilley Immigration Detention Center is that generous. We wait in a line as a group to reach the ticket window. One by one. We show our orders to ticket officials. Our orders state our sponsor’s name and phone number. Mine has Tio Nando’s name and his cell number here. They issue us each tickets. We keep our orders with our tickets careful not to let them out of reach, preferably in hand.

Women in aprons that read “Bus Station Ministry” show us what section of the small grimy bus station we should sit in. In this section only. We sit. We put our bag on the floor or on the seat next to us if no one needs to sit there. Setting our bags on the floor is bad luck, we mexicanas believe but we gotta do what we gotta do. We wait. We go to the restroom if we need to. Most of us need to. If not to use the toilet, to look ourselves in the mirror and splash our face. Maybe rub water under our arms. Beneath our bras. We return to our section to wait. Not very long. We all have been waiting so very very long to get this far. Then the Bus Station Ministry women come to us, one by one.

There are lots of kids with mothers. If I wasn’t in my stupor I’d tease them, I’d play with them, I’d wiggle my fingers at them, I’d make funny faces at them, I’d sing for them. But I can’t.

Technically, at seventeen, I am a kid travelling alone. But I am treated like an adult, without kids. I guess I aged. I felt like a kid. Or like the kid I never was at Hisperia where I could do what I wanted whenever I wanted wherever I wanted. Here everything is about control of me. Us. U.S. Where to stand, where to sit, when to go to the bathroom. Control. But the woman who comes to me with her “Bus Station Ministry” apron treats me differently. She is kind. She cares about the papers I hold. She asks my permission to look at them. She cares about where I am going. She kneels next to me, on the dirty floor, and onto my lap she places a piece of paper with a map on it. A map of the United States. Not “double you es” like WS15641616CE, one of my other time travel terrains. The United States of America. You Es A. “I am Aliena” equals “You es A.” “You are Aliena.”

Mexico is the United Mexican States. We are both United States. And America is the word for Canada and Mexico, not to mention Brazil and Ecuador and Peru and Paraguay and Uraguay and the others. We are all America. But this country in which I now sit allows itself to call itself “the United States.” Or “America,” alone. Like there aren’t other Americas. How rude!

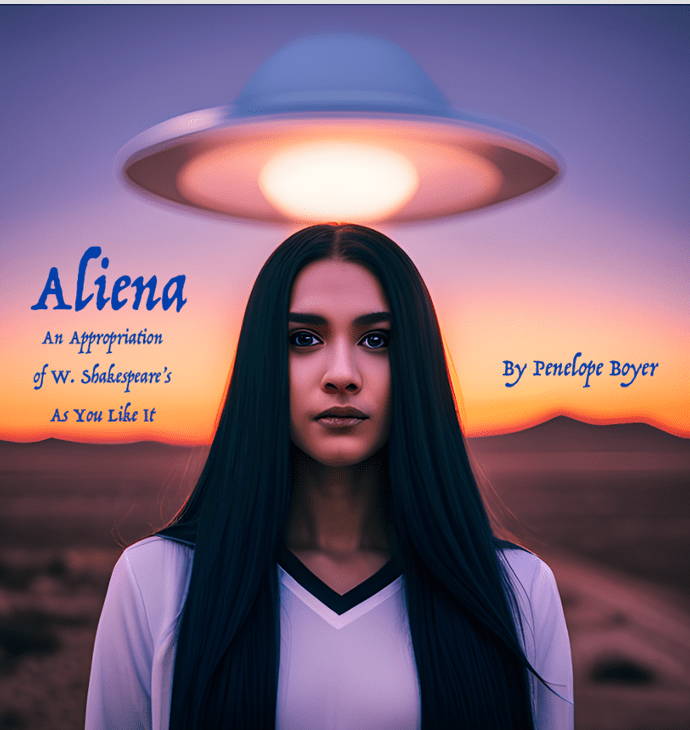

But here I am. My orders say my name is Celia. But I feel I’m aliena. I feel alien. More alien here than I did in the galaxy I visited. I’m Aliena. Aliena in America.

Anyway, the apron woman has laid a map on my lap of the U.S.A. The apron woman treats me as though I might never have seen a map before. I don’t especially appreciate that, but I’m not gonna call her out on it cuz otherwise she’s doing great. She circles “San Antonio” saying that’s where we are now. Then she looks at my tickets. She circles “Las Vegas,” saying that’s where I’m going. She’s not sure she’s being understood by me. I tell her in my fine English that I speak English fine. She marvels at how well I speak it. I tell her that my mother was American and that I insisted on learning English, so I’ve spoken it since I was a little girl. I can tell she wants to ask me about my mother, but she stops herself. It’s almost as if she’s been told not to inquire. I later learn that’s exactly what it is. They are not to learn too much about us because of our situation as asylum seekers. They’ve been told not to take pictures of us in any way, shape or form and not to give anyone any information about us because even the smallest bit of intel could get back to the people and places and things we are seeking refuge from.

Instead, she explains to me each stop I need to look out for on my ride, each transfer I need to make, and she marks them on the map. Mine will be a 35-hour sojourn with stops in Mason, San Angelo, Big Spring, Lubbock, Plainview and Amarillo in Texas; Lamar, Colorado Springs, Denver and Grand Junction in Colorado; then Green River and Parowan in Utah before I reach Las Vegas, Nevada. May as well be twenty days, I think. Then the apron woman stands, steadies herself on my shoulder cuz she’s a bit old. I clumsily stand up beside her and give her a huge hug. I hold her close to me longer than I should have maybe, and when we separate, she tells me with her finger, sensitively, to wait.

She returns moments later with a backpack which she hands to me like a gift. I accept it and I find a smile for her in exchange. It seems so much more durable than the bags they issued us in Dilley. Those “Here Everything’s Better” bags. She unzips the knapsack in my lap to show me what’s inside: a blanket, some sandwiches, a refillable water bottle, hand sanitizer, four disposable masks, feminine hygiene products. Were I a kid that looked like a kid, I would also get a toy—a matchbox car for boys or a cloth doll for girls. And every child seems to get a stuffed animal. I ask the woman if I can have a stuffed animal. She brings me a rabbit. Un conejo. A cute little comforting companion. A small grey bunny, really plush, soft enough to reach my heart. I tell the apron woman “thank you.” Then she’s off to the next person to have a map marked and a backpack given.

PRESENTATION

Mennonite Church ~ Casa de Maria y Marta (Pastor John Garland)

Chapter 17

Hi. My name is Aliena and I’m an alien. I remember being dropped from a disk in Dilley,

Texas where I was taken to an immigration detention center. I wasn’t exactly dropped. I sorta slid through a shaft of light to the rough surface of earth. When I look up at where I came from, I squint and see a disk disappearing into the high dry hot sky. In the detention center I hear about these meetings. Y’all come together to face your identities and agree to manage from day to day. That is how I have chosen to live this life: day by day—well, night by night. If this is what they call a religion, it’s mine. I’ve also come to revere that lady of Guadalupe. From what I have heard, she appeared–like me—as an apparition on this earth, from this same high dry hot sky. I heard she slid down that same shaft of light. Well, not the same one. But she slid through a shaft of light to get here–like me. Imagine that—in all those robes! Not that I’m some saint like she is, or whatever she is. But she also disappeared, as may I. Trouble is, I have no idea what day it is I’m living. They said, “my time,” but I’m not sure they know what they are talking about. I count the nights. The nights are my time, all twenty of them. We sleep on floors under shiny silver sheets. We cover ourselves with water from a wall once every several nights or so, stripped. Or maybe those are days. We eat what is fed to us off disks on a tray. In my dreams, I see a girl named Celia. She is happy and dances in spaces dense with trees and green. There’s a crop being covertly cultivated. Her life is a secret. Her family tends this crop carefully, day by day. I never meet this Celia of my dreams. Something dreadful happens to her. I don’t see it happen, but I know it has happened cuz she flees her family and her happiness in the green. Still, I see her there, in the green, before this event that makes her escape. I see her only as happy with her friend, also female, and only sense she’s no longer free cuz she flees. I never meet this Celia but the papers they find on my physical body in Dilley are hers. So, I became Celia though I think of myself as Aliena. Aliena is the name given me by WS15641616CE. And after those twenty nights, Celia’s name is called for departure. As Celia, I speak Spanish and as Celia I tumble into a big yellow metal vehicle crowded with others and am taken norte to San Antonio in Texas everyone says. In San Antonio we reach a building with a huge long dog in white on blue like the changing clouds in the big Texas sky I’ve been staring at because beyond this sky is the galaxy I visited. Beneath the directional dog are the letters, “B,” “U,” “S” in blue on white like the crappy fake fiber shopping bags they gave us in Dilley—abuela used better bags than that for marketing—they’re all marked “H,” “E,” “B” and I wonder if that stands for “House of the Evil Brother,” but written on them also is “Here Everything’s Better” which must have been printed just for us. Us people getting on the bus. Here everything’s better. Everyone keeps saying that about the States. Where we’re going. Here everything’s better. Here everything’s bigger. Here everything’s broken. Here everything’s bitter. Here everything’s buttered. Here everything’s battered. Here everything’s braver. Here everything’s beautiful. Here everything’s bad. Here everyone’s bad, here everyone’s battered, here everyone’s broken. There were other long vehicles like our big yellow metal one. Buses. My English is subconscious but impeccable. Osmosis from two hours on that disk? I don’t know. Still, as Celia, I speak freakily fluent Spanish. And English. And some tongue I don’t readily recognize—maybe a disk discourse. Dunno.

At this so-called “terminal,” which I’m sure means “end,” we are to start our new lives. That’s what people kept saying. Start a new life. So that’s what I did. In Spanish. I let the people in the terminal think I can’t understand their English. They tell me in clumsy Spanish-inflected English, “You-are-going-to-las-vegas-nevada”—meadows, snow-covered. Hmmm. Sounds cold like they say el norte is. I’m shown on a map my itinerary which includes a long time in el paso, “the step,” before arriving in the snow-covered meadows a day later. Actually, I arrive at night.

“What’s your name?”

My name is Aliena and I’m an alien. In America, I am Aliena. In Arden, I am Aliena. In Stratford, I start as Celia, and Celia loved Rosalind. Never two ladies loved as we have. But when I became Aliena, she is Ganymede, and I grow to hate her. She’s suddenly bi and I just can’t bare to watch it. That’s why I get blurrier and blurrier in that play until he has me suddenly hooking up with Olivo, is it? Or Carlos? Gross. All that stuff about “no sooner”: no sooner met but they looked, no sooner looked but they loved, no sooner loved but they sighed, no sooner sighed but they asked one another the reason, no sooner knew the reason but they sought the remedy. I guess that means we fucked. Before that grand ol’ mass marriage at the end. Pass the Kool-Aid, please. Fucked out of wedlock, as it were. A lot of that goes on in this play, his play. Play. Play. Play. Seriously. Play? Not much fun at all.

“How old are you?

Hard to say. For four hundred years I have been stuck in this play, this drama, this relentless role. Since 1623 CE. Four hundred years exactly, huh? Well, I’m actually older than that. It was in 1623 CE the First Folio was published. Meaning the play could receive pay. I must have been underway since 1599 or 1600 CE, they think. I think I’m seventeen there. In the play. But when I was abducted I dunno what world time zone I was in. What world I was in. Or who’s spaceship it was or whatever. Whatever celestial time zone I travelled to and when that was or where we orbited and when–but that could mean I’m not seventeen. Well, by some accounts I could be 417 years old or 420 or around there, see?

Borderlands Shakespeare Colectiva – 10 minutes

Chapter 21 (6 minutes)

“I gotta kill Ganymede,”

“Kill him?”

“I gotta get rid of that pretentious name. At the detention center the gringos thought it was some Spanish name. Ganymede’s not me—it’s a racehorse name. I’m no stallion.”

“Sure you are!”

“I need a good solid boy’s name. Gany… Sounds like…Gary. Yes, Gary. Heigh! Gary Mead. That’s it! That’s me! I saw on the map—Las Vegas is near Lake Mead—the largest manmade lake in the entire U.S.A. ‘America’s First National Recreation Area!’ It feeds water to like all of Nevada, all of California. It’s the perfect name, actually.”

“You wanna be called ‘Lake Mead’?”

“No! Gary Mead! Me—I’m Gary Mead! Still sounds like Ganymede so maybe our luck won’t wear off.”

“Luck?”

“Yeah, we’re going to Las Vegas! We need Lady Luck on our side!”

“Rosalind, dear, how serious are you gonna go with this boy stuff? I’m not sure I approve.”

“You know what, Celia, my dear—I mean, Aliena—look how you’ve gone far from your

name, too. Another galaxy, right? Maybe I should take this step too—maybe I should become a boy, for real. The ultimate disguise. Worked well for me at Karnes. Not a single man guessed I was a girl. Flatten my façade further—you know—get rid of these tiny titties, build a bottom— you know, grow a cock—whaddyathink? Honestly?”

“Honestly? I can’t believe what you’re saying. You’re gonna kill Rosalinda to become Gary Mead?”

“I AM Gary Mead! If you are Aliena, then I am Gary Mead!”

“Yeah, but I didn’t become a Fact! Aliena is still fiction. I think. Hmmm. Well, maybe not. But I am certainly not a funny looking space age scarecrow: I AM NOT A Fact!”

“Honey, I don’t know what the heck you’re talking about!”

“I know. You weren’t there. You were off being a boy. In the men’s unit. I didn’t get to see you. I didn’t get to sleep with you. I was beamed down from that gadgetry in the air and where were you? Nowhere to be seen. Gracias a dios it all happened so fast. In there for like two hours or whatever it was.”

“Two hours? We were detained twenty days! The max for kids. We’re still kids, you know.”

“Maybe you were in there twenty days. Not me. Not Aliena. Maybe you and Celia were in there for twenty days—you can both rot in hell as far as I’m concerned. I heard some people are in custody there for years, that could be you two as far as I’m concerned. Abandoning me like that and not caring where I had gone or whatever. I was there two hours, tops, in that detention center. That’s all I could take.”

“You really are Aliena, huh?”

“Damn straight. Well, not exactly straight, but you know what I mean. Well, maybe you don’t know what I mean anymore. Gary Mead. So now we’re a straight couple? Gary and Aliena?”

“O, Celia! I mean, Aliena!”

“You mean Aliena! No, I’m mean Aliena! Watch and see how mean I can be!”

“Don’t be mad.”

“Mean, not mad. I’m as sane as I ever was. Sane as I ever was. Isn’t that a song? Some Talking Heads stuff?”

“You know, mead is a fermented honey drink. It suits me. The former Rosa Linda, prettrose—bees attracted to me. Remember, most bees in a hive are girls serving a queen.”

“How could I forget?”

“Though mead can be sweet or semi-sweet. I did my research. In the computer lab. Long lines to get online but I got there a bunch of times. And you’re lucky I’m not calling myself Dr. Elwood Mead cuz that’s who Lake Mead is named for. He created the nearly 250 square mile lake: ‘The Engineer Who Made the Desert Bloom.’ Today, twenty-five million people in Nevada, California and Arizona drink water from Lake Mead. But its water volume is declining due to decades of drought and loss of Rocky Mountain snowmelt—both caused by the climate crisis. I also researched Dilley but there’s not much there besides your detention center. I researched Vegas. That’s what they call it—not Las Vegas—just Vegas. Lots of tourists. They call it Sin City. Marriage Capital of the World. Divorce Capital of the Americas. Entertainment Capital of the World. Gambling Capital of the World. And Neon Capital of the World. Sounds like the right amount of flamboyance for Nando, no? If they’re not homophobic, right.”

Nowhere’s as homophobic as Mexico, I think.

They shoot gays places.

Rico just about shot us. And Nando. Okay, we didn’t get shot—but only cuz we’re family! Get it? Isn’t that what gays call each other–family? Now I sound like Toque.

Exeunt [ek·see·uhnt].

Thank you all for coming. I hope you’ve enjoyed these bits of ALIENA. Are there any questions for any of us. I’m sorry Michelle Rumbaut from the IWC needed to leave early, but if there are any questions for any of us I think we could take a couple minutes…